We have moved to planbienen.net >>>

Author Archives for Sumugan

Gift from the Bees

[Script for parting performance presented by Sumugan Sivanesan at ZK/U, 25 September 2014]

Hello and welcome to our Openhaus. All of us at ZK/U have been busily anticipating this evening’s schedule, and I would like to begin the tour by drawing your attention to those that might have been the busiest of us all, but have now retired for the evening—the Moabees. Over the summer there has been some buzz around die Bienen in the city and the extent to which Bienenvolke are appearing in each and every kiez. It seems that reports of scores of dead and disappearing bees over the last few years have revived our interest in these long-time cultural companions, calling attention to the ways in which we all profit from their presence.

The phrase ‘robbing the bees’ is often used to describe the task of collecting honey from beehives. Honey may well be sought after as a ‘nectar of the gods’, but is in the first instance food made by and for bees from the nectar they collect from flowers. Recently, Tessa and I were talking to a beekeeper who described the honey she had extracted as ‘a gift from the bees’. This Imkerin said that the bees permitted her to take their honey as long as she agreed to pass it on. She gives jars of honey to friends and relatives, and to tradespeople as a reward for a job well done. Such gifts spotlight the interplay of goodwill and obligations that bind us to one another and are in excess of more rational economic relations.

Humans have harvested honey and cultivated bees since the earliest recorded civilisations, however for many of today’s beekeepers honey is simply a ‘sweet bonus’, a byproduct of the crucial pollination services that these and other insects provide. In the current eco-cultural climate bees are often portrayed as a benevolent species—‘the good bee’ brings the world into abundance and maintains the conditions on this planet in which we thrive. If we believe that by improving the lives of bees we also improve our own, then what kind of lifeworlds would emerge if we pegged our progress to bees?

Berlin has a reputation as a bee capital. In the past, the city’s beekeepers lobbied for the planting of certain trees that would provide food for bees… their success can be read in street names such as Unter den Linden, Birkenstrasse and Kastanienallee. More recently installing hives atop significant buildings such as the Abgeordnetenhaus, the Berlin Opera and of course right here at ZK/U, not only locates bees in the heart of the city but brings them into our social consciousness. Today European beekeepers have been instrumental in having particular insecticides, known as neonicotinoids, banned in the EU, reducing the mortality rates of bees and wilfully keeping the prospect of a world without bees at bay… as one local beekeeper puts it, ‘intervening politically on behalf of the bees’.

Honeybees are social beings capable of collective decision-making and action. They are creatures of extraordinary strength and endurance that give their lives for the hive and are often used to symbolise patriotism and hard work. The sociability of bees has been read as a metaphor for both social collectivism and capitalist industrialism, as well as to argue for and against the value of individualism. Our fascination with bees has inspired the sciences, arts and philosophy, so might a bee-led social turn, in turn shape our wellbeing?

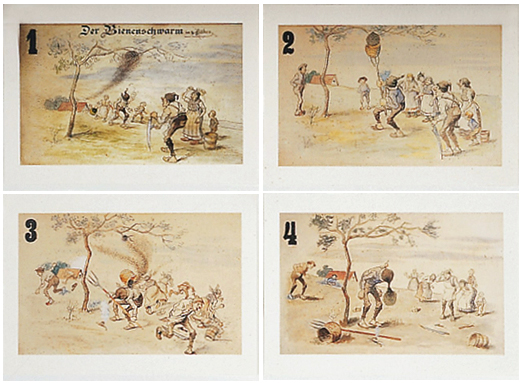

Whilst it is unlikely that if all the bees of the world suddenly died, we would soon follow, such a scenario would spell catastrophe for both our habitats and industries. Little is known about the effects of bees on the systems that support arable land, but we can be sure that yields of, say, almonds in California or coffee in Costa Rica would collapse overnight. As the once well-stocked shelves in our food halles and supermarkets began to empty out, would ideas that we associate with bees, such as social cohesion and cooperation, also disappear? As a consequence, imagine if organised and once industrious workers arose as a swarm of vengeful killers!

A principle of classical economics known as Jean-Baptist Say’s law states that ‘supply creates its own demand.’ According to this logic, supply precedes demand and seeds desire. Now into my last week at ZK/U, and with Tessa already back in Sydney, I find myself with an over supply of raw local honey—more than I could possibly consume before I too must leave. As a parting gesture and in the spirit of ebullience and abundance Tessa and I would like to pass this bounty on to you. Consider it a gift; from ourselves and the beekeepers, and by extension a gift from the bees.

[Cue music]

Video: Faraz Anoushahpour

I don’t want your money, honey…

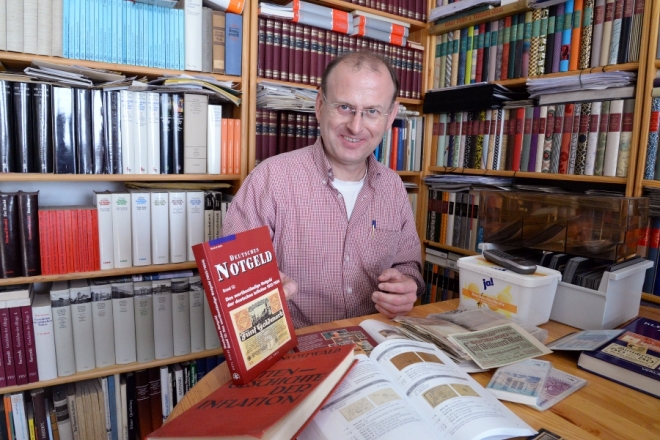

We recently spent some time with the economic historian and bank bill broker, Winfried Bogon, whom we had contacted to purchase notgeld or emergency money that was used in times of fiscal crisis such as hyperinflation.

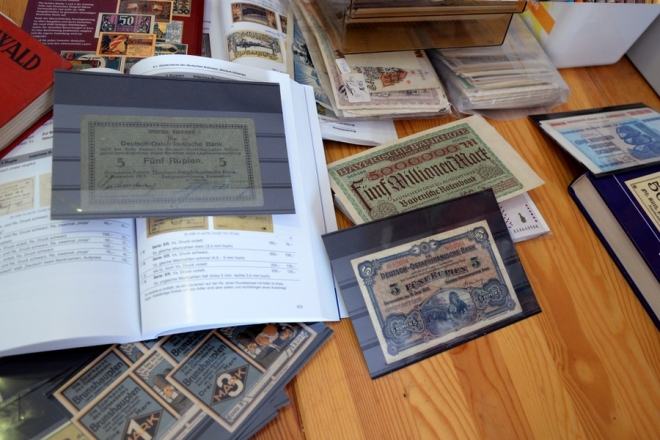

A well known episode of hyperinflation occurred in Germany in the 1920s. When World War I began in 1914, Germany ceased to back its currency with gold reserves. As the conflict was expected to be short, the Empire funded its efforts by borrowing, rather than with savings or taxation, leading to a steady devaluing of the Deutschmark as the war drew out over four years. The end of the war saw the demise of the German Empire, which was succeeded by the Weimar Republic in 1919 that became responsible for paying the massive reparations demanded by the Allies under the Treaty of Versailles (1919). This debt was to be paid in gold-backed hard currency, not the rapidly depreciating ‘paper Marks’, as well as in commodities such as coal, iron, steel and wood.

One immediate measure taken to finance these payments was to print more Marks in order to buy foreign currency, which was in turn used to service the debt. As no other workable solution was found, this initial inflation soon spiralled into hyperinflation as more marks were released into circulation. Furthermore, annexed territory and the required reduction of the German army led to unemployment and volatile political conditions. When it became apparent that Germany would be unable to make the required payments, Allied forces occupied ports and industries in the Rhine, such as the industrial Ruhr region, to ensure the reparations were paid for in goods. As workers undertook strikes, more money was printed to pay for their means of passive resistance further excacerbating the fiscal crisis. The price of a loaf of bread illustrates these effects; in 1922 a loaf of bread cost 163 Marks. By September 1923, it cost 1 500 000 Marks and at the peak of hyperinflation in November 1923, a loaf of bread cost 200 000 000 000 Marks. Other anecdotes published in a US report in 1970 state:

By mid-1923 workers were being paid as often as three times a day. Their wives would meet them, take the money and rush to the shops to exchange it for goods. However, by this time, more and more often, shops were empty. Storekeepers could not obtain goods or could not do business fast enough to protect their cash receipts. Farmers refused to bring produce into the city in return for worthless paper. Food riots broke out. Parties of workers marched into the countryside to dig up vegetables and to loot the farms. Businesses started to close down and unemployment suddenly soared. The economy was collapsing.

Notgeld were issued during this period by townships, industries and utilities. Forms of emergency and community currency came into use across many parts of Europe and are still used today in some places. Valid for short periods of time, Notgeld were to be spent not saved, nevertheless according to Winfried, German Notgeld and a subset of bills known as Seriensheine were unique as they were often designed to be collectable. Featuring commissioned illustrations, etchings and employing sophisticated printing techniques, these bills present an ephemeral pictorial history of financial crisis. revealing the desires and opinions of communities during these times of distress.

Amongst Winfired’s collection were notes or coupons issued by merchants valid for basic supplies such as flour or sugar, prompting the money expert to recall times when pieces of coal were more valuable than coin as they had a greater use value. We had already heard from several beekeepers that in the DDR the state bought home-produced honey from citizens for a fixed price, suggesting that the local tradition of keeping bees was at one time an important alternative source of income. Such accounts piqued our interest to use honey in lieu of money.

The American money manager George J. W. Goodman, writing under the moniker Adam Smith, commented that when one US dollar became equivalent to one trillion Marks in 1923, the German currency stopped making sense. For some people, having to calculate such fantastic figures for everyday exchanges brought on a nervous affliction known as ‘Zero Stroke’, a condition which compelled sufferers to write endless rows of zeros or ciphers. Eventually a simple cure for these hyperinflationary maladies was found in 1923, when the Reichsbank issued a new note to replace the Mark. One Rentenmark was exchanged for one billion of the old currency, striking nine zeros from the latter and prompting the ‘miracle of the Rentenmark’. As the Republic was still rich with working mines, farms, factories and forests, the new currency was backed by property mortgages and factory bonds that effectively speculated on the future productivity of the state—a form of wishful thinking known as credit. Goodman notes that the word ‘credit’ derives from the Latin credere, ‘to believe’, to proffer that the German people must have desperately wanted to believe. Winfried concurred, and it seems we all agree; ‘money is a matter of belief’ that is fundamentally a system of trust.

References

Kosares, Michael J., 1970. ‘The Nightmare German Inflation.’ Scientific Market Analysis.

Smith, Adam, (Goodman, George J.W.), 1981.‘The German Inflation, 1923.’ In: Paper Money, pp. 57-62.

Non-human Rights

‘Killer Bee’ movies emerged as a popular strain of ‘creature feature’ films in the Cold War era of the 1960s. Films such as The Deadly Bees (1966), Genocide (1968) and The Swarm (1978) established a genre based around formulaic ‘nature’s revenge’ plot lines in which insects, often mutated in scientific experiments, escape from laboratories to attack and kill human protagonists. In The Bees (1978) swarms of mutant bees bring down military aircraft, target politicians and deliver an ecologically-driven ultimatum to the United Nations via a human interpreter. Such fantastic narratives can be read as popular cautionary tales about the modern sciences empowering humans to ‘play god’, underpinned by a Cold War fear of biological warfare and the scientific supremacy of ideological rivals. Curiously these films attribute direct agency and political action to swarms of angry, organised non-human actors, entertaining the prospect of non-human rights.

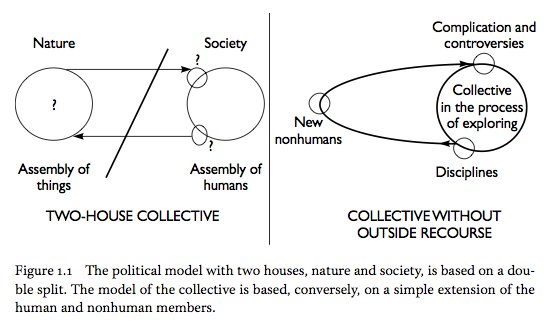

The phenomenon of disappearing bees synonymous with Colony Collapse Disorder has compelled lobby groups such as Mellifera e.V. in Germany to interfere on behalf of this ‘subaltern species’ in human affairs, resulting in a temporary ban on the use of neonicotinoid insecticides in the EU, which is soon take effect in the US as well. In his book The Politics of Nature (2004), Bruno Latour details his vision for a collective yet-to-come of human and non-human agents that would supersede the society/nature divide upon which modern institutions are founded.

Might this most recent phase of human-bee relations provide an entry point to consider how such ‘multinatural’ political associations are actually taking shape? Furthermore, is it only in fiction that a species capable of collective decision-making and with which human cultures share a long history–and also food–could have ‘thought’ to take actions in order to change our behaviour?

Might this most recent phase of human-bee relations provide an entry point to consider how such ‘multinatural’ political associations are actually taking shape? Furthermore, is it only in fiction that a species capable of collective decision-making and with which human cultures share a long history–and also food–could have ‘thought’ to take actions in order to change our behaviour?

This Planetary Conjuncture

To call ourselves geological agents is to attribute to us a force on the same scale as that released at other times when there has been a mass extinction of species. Dipesh Chakrabarty, The Climate of History: Four Theses, 2009.

Dipesh Chakrabarty begins his essay The Climate of History: Four Theses (2009) by asking his readers to imagine ‘a future without us’, raising the prospect of human finitude as a potential (and some would say inevitable) catastrophe that appeals to a notion of human universals. The historian argues that scientific consensus regarding human induced climate change has facilitated a significant shift in our systems of knowledge. Humans who have evolved to cause significant changes in the Earth’s atmosphere, environment and ecological systems have become geological actors over recent periods of expansion and industrialisation, as put forward in the Anthropocene thesis. In doing so humans have instigated a series of ecological reactions that may potentially render the planet inhospitable for their continued advancement (and thereby suggesting the limits of capitalism). Chakrabarty lists recent droughts, cyclones, brush fires, crop failures, melting glaciers and polar ice caps, the increasing acidity of seas and damage to the food chain as some of the consequences of recent human activities and innovations. In light of such developments, Chakrabarty urges his readers to reconsider the discipline of human history, which over the course of its development occurred apart from natural history, to recognise human agency in changing the most basic physical properties of its host planet. At a public lecture delivered at Haus der Kulturen der Welt Berlin, June 2014, the influential scholar pressed for another kind of historical thinking in which nature might act as a co-author.

Paintings of beehives in the tomb of Pabasa, Valley of the Queens.

In her contribution to the Reaktion Books animal series, Bee (2006), Claire Preston refers to pictorial records depicting the cultivation of bees to claim that apiculture originated with the ancient Egyptians as early as 2500 BC. She continues to discuss other pre-common era records of bee cultivation and honey hunting across Europe and India, describing a significant and even symbiotic co-existence between humans and bees through the ages. Indeed bees and other pollinator species are essential to the human food chain. More than one-third of the world’s crop species, such as alfalfa, sunflower and numerous fruits and vegetables, depend on bee pollination. Furthermore, scientists estimate that animal mediated pollination is required for the reproduction of nearly 70% of the world’s flowering plants, including between 60% and 90% of wild plants.

In recent years the mass disappearance and death of worker bees from managed hives, a syndrome known as Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), has raised awareness of the roles and challenges faced by bee populations in the industrialised world. Scientists have not been able to narrow down a single cause of CCD, rather attributing the sudden death of bee populations to multiple and interactive conditions. These include the prolonged use of insecticides and in particular neonicotinoids; new parasites and pathogens such as Varroa mite and Nosema; environmental stresses including a lack of biodiversity in monocultural farming environments; and effects of climate change such as season creep. The phenomena of CCD and the lack of accurate data about global bee populations and other pollinator species may have inspired a renewed interest in urban beekeeping and community innovations such as Open Source Beehives. Bee lobby groups, such as Mellifera e.V. in Germany, that ‘interfere’ politically on behalf of bees, have been successful in having a temporary ban placed on the use of neonicotinoids in the EU, although not yet in the US where CCD has had a greater impact.

If we posit bee colony mortality against the expansion of human populations and their geological effects, does the prospect of the extinction of the former species necessarily spell catastrophe for the latter? The artist Ally Bisshop suggests that precarious bee populations are allegorical of human finitude as both species are effectively subservient to the sun. If pitched as a contest between populations of human, bee and other heliocentric species with regards to their ability to inhabit, extract resources and manipulate their environment, Chakrabarty reminds us that the eventual decline of the human species that can be glimpsed in the death of bee populations is not ‘a crisis for the inorganic planet’ and would not spell disaster for the Earth and its most prolific matter.

What are the implications of Chakrabarty’s call for another mode of history, in which nature might be a co-author, for our own practice that concerns social relations and exchange? How are such interspecies relations translated as politics and what is the potential for non-human agency in the expanded notion of culture that Chakrabarty suggests?

References

Bisshop, Ally, 2014. ‘The Bees Will Tell Us’ (draft copy). Also available in Bisshop, Ally and Messih, Gemma, 2014. Eventually the Sun will Consume the Earth.

Preston, Claire, 2006. Bee. Reaktion Books, London 2006.

–

To Bee: Biohybridity and learning the ‘language’ of bees

During the week we met Anna, a beekeeper at Prinzessinnengarten, who wondered what it would be like to be a bee for a day. Karl von Frisch discovered that bees possess a ‘language’ through a series of experiments he began in the 1920s. Now scientists following in his wake are attempting to communicate with bees using robots that will ‘live’ amongst bees and with a view to influence their decision making processes and behaviour. Such propositions bring to my mind China Miéville’s science fiction Embassytown, in which humans co-habiting a planet with large insectoid hosts shift the parameters of language across both species—the story’s protagonist is a simile that functions as part of an alien language without the faculty to lie.

The RoboBee Project headed by Raul Rojas at the Freie University Berlin have developed a honeybee robot that can do a basic waggle dance. As can be seen in the segment below, these dancing bots could potentially be used to tell real bees to fly to specific locations.

Project ASSIS|bf coordinated by Dr. Thomas Schmickl of the Artificial Life Lab at the University of Graz are developing robots that will be able to communicate, adapt and evolve to ‘live’ amongst populations of bees and fish. By focusing on ‘swarm intelligence’ the project proposes to pioneer methods by which humans can interfere in animal societies in order to manage the environment. Schmickl lists various benefits of doing so, ranging from pest control to agriculture, but also considers contemporary human, social media affected society to be a social cyborg in itself. Thus, he reasons, model systems in the lab for studying mixed-societies of robots, algorithms and social organisms are crucial to understanding our own human society.

Thomas Seeley’s Honeybee Democracy recounts the the biologist’s lifelong study of honeybees. Seeley, writing in a very personable style, describes how he came to understand the hive as a collective intelligence, and the bee swarms as ‘a kind of exposed brain that hangs quietly from a tree branch’. In a blog post for the Harvard Business Review he offers what we might learn from bees’ collective decision making:

1. Remind the group’s members of their shared interests and foster mutual respect, so they work together productively. The scout bees know instinctually that their interests are aligned toward choosing the optimal home site, so they work together as a team. There are no clashing curmudgeons in a bee swarm.

2. Explore diverse solutions to the problem, to maximize the group’s likelihood of uncovering an excellent option. The scout bees search far and wide to discover a broad assortment of possible living quarters.

3. Aggregate the group’s knowledge through a frank debate. Use the power of a fair and open competition to distinguish good options from bad ones. The scout bees rely on a turbulent debate among groups supporting different options to identify a winner. Whichever group first attracts sufficient supporters wins the debate.

4. Minimize the leader’s influence on the group’s thinking. By functioning as an impartial moderator rather than a proselytizing boss, a leader enables his group to use its combined knowledge and brainpower. The scout bees have no dominating leader and so can take a broad and deep look at their options.

5. Balance interdependence (information sharing) and independence (absence of peer pressure) among the group’s members. Only if ideas are shared publicly but evaluated privately will the group be good at exploring its options and making good choices. Scout bees share freely the news of their finds, but each one makes her own, independent decision of whether or not to support a site.

Illustrator, author and beekeeper, M.E.A. McNeil’s summary of the book can be read here and here. Tom Seeley’s 2011 lecture at Cornell University is below.

Frei-bees

Biologist and biodiversity researcher Dr Casper Schönig manages a number of urban beehives around Berlin, including some we visited in the garden at Cafe Botanico over the weekend. He traces the tradition of beekeeping in Berlin through to the DDR, when honey functioned as an alternative currency and could be sold back to the state at a fixed price (Annette Mueller, founder of Berliner Honig, an association of local beekeepers, tells a similar story). Following the fall of the wall, urban hives dropped out of use as other economic opportunities arose, contributing to the decline of the local bee population. Schönig is skeptical about the significance of Colony Collapse Disorder in Europe, and indeed about any overgeneralised approach to the various problems faced by bees in different parts of the world. Though today in Berlin there is only one-third of the number of city beehives active in the 1950s, it seems that urban beekeeping is currently experiencing something of a revival, following campaigns such as Berlin Summt! to install beehives on rooftops around the city.

Germans are in fact amongst the world’s largest consumers of honey. Claire Preston in her contribution to the Reaktion book series on animals, Bee (2006), claims Germans consume up to 4.3 kg of honey per capita compared to 0.5 kg in the US (citing figures from the American National Honey Board; Preston 2006, p. 48).

Image sourced from Prinzessinnengarten blog.

At Prinzessinnengarten, beekeeper Heinz maintains foundationless hives, foregoing the pressed wax comb templates that are common to domestic hives. Ridges on the inside of the roof of his hanging ‘coffin beehive’ provide prompts for the bees to build combs orderly enough for Heinz to inspect and rob. He believes that the smaller combs built in these hives allows for better protection against parasites like the notorious Varroa mite. The brood occupies the front section of the box which Heinz accesses from below, and can expand into the rear of the kiste to store honey. Heinz claims these hives also allow more room for the bees to perform their waggle dance. Heinz doesn’t prevent his bees from swarming, nor does he remove the drones, and only minimally intervenes for hive maintenance, using organic acids seasonally to protect against parasites. He harvests honey once in the season, usually around mid-summer, to allow the bees time to replenish their honey stocks before they ‘overwinter’, preferring not to feed them sugar water or supplements.

Nebraskan beekeeper Michael Bush endorses a similar approach of ‘lazy beekeeping’ that simply allows bees to do their thing with minimal interference. Bush, like Heinz, believes these methods result in healthier, cleaner hives and encourage stronger strains of bees to flourish.

North America is afflicted by Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), the threat of Africanised Honey Bees and numerous other pests and diseases, which have led beekeepers to become reliant on pesticides and regulatory processes. Bush observes that the depletion of localised feral bee populations and beekeepers buying queens from a small group of breeders has resulted in a significant reduction of the bee gene pool on the continent. Rather than practice such precarious methods, Bush has sought other means by which to keep his hives free of mites and diseases. He now maintains what he calls ‘natural comb’ hives, producing smaller combs than those made by ‘normal’ bees, and advocates for others to similarly regress their hives. By removing the template wax combs from hives and allowing bees to draw their own, successive generations of bees become smaller. This approach to beekeeping, while still a means of harvesting honey for human consumption, emphasises healthier hives and stronger bee generations over maximum honey yields, and might be considered more benign(!).

Might such shifting dispositions represent an entry point from which to think about an interspecies ecologically-focused approach to urban agriculture, economics, science and politics?

“Geruchssinn der Bienen” by Karl von Frisch (1927)

The film “Geruchssinn der Bienen” by Karl von Frisch (1927).

Source: IWF/C56. By kind permission of IWF.

Sourced from: Tania Munz, ‘Numbering Bees—A History of the Bee Language: Karl von Frisch, the Honeybee Dances, and Twentieth-Century Sciences of Communication.’

Karl von Frisch sensationalised science by interpreting the honey bee ‘waggle dance’ through a system of observation, marking and numbering. He discovered that through this elaborate ritual bees communicated the distance and direction of food sources in relation to the sun, and established that bees were able to distinguish scents, perceive colour, and possessed an innate sense of time. Such discoveries challenged longheld notions of the human-animal boundary by revealing that humans were not the only species capable of developing a sophisticated language.

The German physiologist eventually won a nobel prize for his work on the honey bees. According to science historian Tania Munz, von Frisch was:

an early and enthusiastic producer of scientific films and used them as tools for observation and demonstration. He often relied on the medium to demonstrate aspects of behavior that lay beyond its direct explanatory reach—black-and-white silent film was called upon to support arguments about the bees’ abilities to discern colors, scents, tastes, and sounds. In a 1927 film, von Frisch sought to demonstrate that the bees can perceive different scents. Here stains left behind by scented oils were called upon to indicate the presence of odors. Thus, another aspect of the project shows how von Frisch bridged the epistemic gaps of the medium by training audiences to read the invisible in the visual language of film.